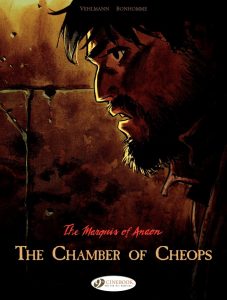

By Vehlmann & Bonhomme

Publisher: Cinebook

ISBN: 9781849182959

Poulain, much to his bafflement, has learned he is to inherit a grand sum of money from a Mr Leone, a gentleman he’s never met, and, it seems, he’s not the only one to receive such a fortune. However, he is the only one who pays a visit to the deceased’s apartments, now bequeathed to the housekeeper who feels greatly out of place in the vast rooms. One room, the bedchamber of Mr Leone, has been completely stripped of its contents which now sit piled in the main living room. Poulain learns this was a last act before Leone excitedly dashed off for Egypt.

Curious, Poulain decides to follow in Leone’s footsteps and attempt to learn what drove the man to give him such a vast amount of money. Met directly from the boat by a man called Charles Ruffin and taken immediately to a Mr Delambre, Poulain is offered the use of Leone’s old residence. There is much courtesy displayed, but Poulain notices he is being watched. It transpires that Leone was interested in a treasure connected to the Chamber of Cheops in the Great Pyramid, and Delambre wants to know what Poulain knows of it. A run-in with a man called Richardson suggests a belief that the ancient Egyptians were far more intellectually capable than the times merit, although Poulain’s questioning of Richardson’s conclusions do not go down well. Poulain is making few friends and putting plenty of noses out of joint, and the more questions he asks the more threatened he finds himself, so perhaps the only answer to the enigma of Leone’s actions lay in the chamber of the Great Pyramid itself.

We may think we live in enlightened times, but there are always questions and answers that suggest yet more questions that some will misunderstand, misdirect or misuse for their own agendas. The nature of science, understanding, and reason is to comprehend a wider knowledge, supported by evidence and critical thinking. We use these tools to dissect and question, formulate theories and hypotheses, and invite others to test our findings. If someone disagrees with a finding then it is up to them to demonstrate why, and if all they can suggest is ‘alternative facts’ or supply no supporting evidence then that’s no argument at all. So if it’s hard enough nowadays to get the populace to appreciate the importance of evidence, and how to discern if the evidence is of any merit, then imagine what it would have been like in the 1700s, where superstition, religious intervention and a general lack of education allowed for a world of demons, monsters and magic as a rational explanation to the world around you.

It’s capturing the beginning of this age of enlightenment that makes this series so erudite and sharp. Poulain isn’t even wholly aware of his own questioning approach, looking beyond glib and shallow thinking for a simpler, workable answer. He’s out of step with those around him, but it’s a step forward none the less. The fact that it’s so wonderfully illustrated enhances the writing all the more. This entire series to date is one I’ll make time to come back to sooner rather than later.

And if you liked that: Try Long John Silver, also from Cinebook

No comments yet.