There can’t be many cartoonists whose work can be said to have changed the behaviour of a nation. Nor too many whose work affected the course of fashion. And not too many, either (just two), who went on to edit Punch. The cartoonist in question is Cyril Kenneth Bird, known to most as Fougasse.

C K Bird (1887-1965) was an engineer in the army till a shell shattered his spine at Gallipoli and he was invalided out, unable to walk for three years. Taking up his pen, Bird got his first cartoons into Punch from 1916 on wartime themes. The name he adopted was French for an unpredictable explosive device, a small landmine of uncertain aim that might or might not hit the mark. That seemed appropriate for cartoons and for him.

He needed a new name as there was already a Bird in Punch. W. Bird was the pen-name of Jack Butler Yeats, painter, writer and brother of poet and playwright WB Yeats. Jack rose to be ‘the most important Irish painter of the 20th century’, Encycl. Britannica (though my preference would be for Paul Henry any day).

He even got to win Ireland’s first Olympic medal through his painting: at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, arts and music were included in the competition at the urging of de Coubertin, keen to recreate the spirit of the original games. Yeats’ Liffey Swim was entered on behalf of the newly created Irish Free State and came home with silver.

But, back in 1916, Yeats was illustrating magazines like Boy’s Own and Comic Cuts, as well as writing for Punch as Bird. Fougasse, meanwhile, went on to become a stalwart of the magazine. By 1937 he was art editor and then actual editor, 1949-53. Most online biographies describe him as the only cartoonist or artist ever to edit Punch. I’m not sure where that leaves Bernard Hollowood (editor, 1957-68), who was also a writer and journalist, but whose first contact with Punch was as cartoonist. His gags appeared in The Times, The Telegraph and The New Yorker, and it is primarily as a cartoonist that Hollowood is remembered.

Style-wise, Fougasse managed to develop in two directions at once. Throughout his career he turned out – as with his Punch covers – artwork that was complicated, busy, detailed, colourful and pictorial.

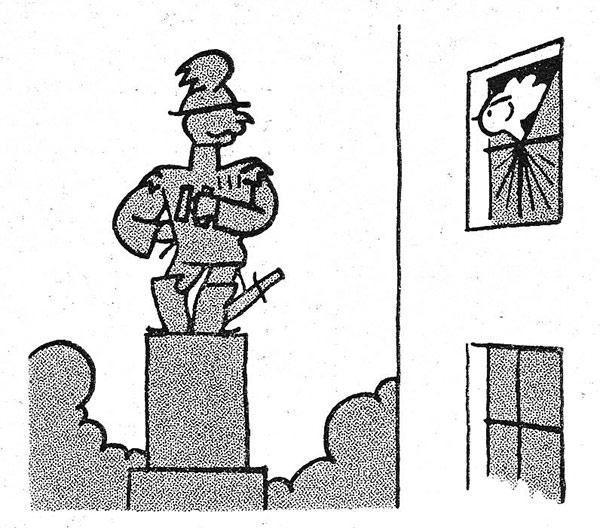

At the same time, he cultivated for simple gags a distinctive spare style that stood out a mile. In all honesty, it’s not my favourite way with cartoons, a bit too stylised, bare and impersonal for me. But I admire his skill in getting so much across in such an apparently quick and simple way. For catching the eye, delivering a joke or conveying a message, it worked brilliantly. For advertising and for wartime propaganda (to which he offered his services for free) it was perfect.

Which brings us back to where we came in. The Fougasse way with swift line and simplified forms was adopted for Austin Reed adverts. It became the hallmark of good tailoring and even fed back into the new looks that he caricatured.

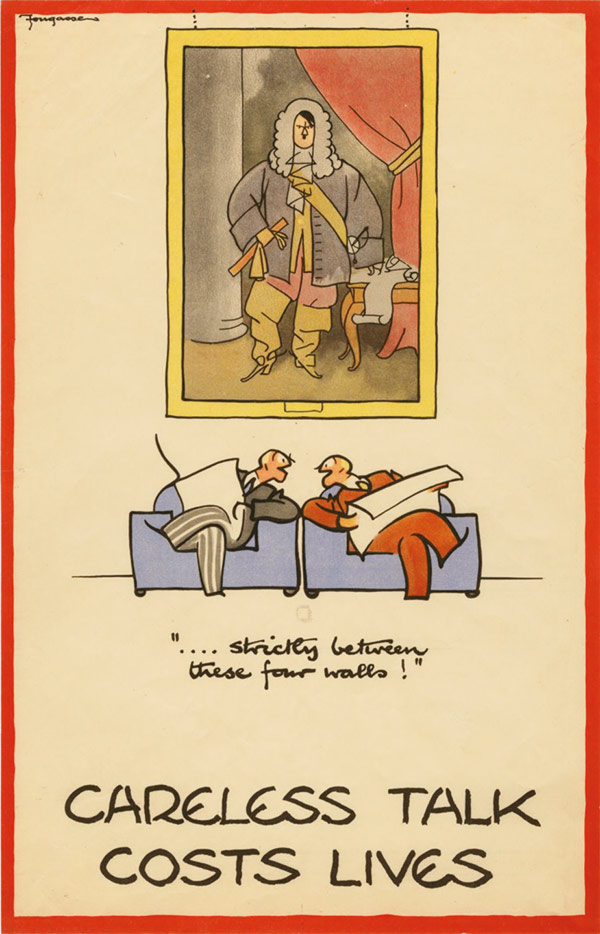

More literally, his propaganda cartoons were printed on dress material for patriotic women. Best remembered still are the cartoons he did for the Careless Talk Costs Lives campaign.

The extent to which the whole country took the wartime vow of silence is fairly astonishing to us today. Husbands, parted from wives for years on end, exchanged barely a word on the subject afterwards. Secrets were kept for a lifetime. Finlay McKay’s book on Bletchley Park tells movingly how firmly lips were sealed. My great-uncle, home on leave from escort duty with Atlantic convoys, turned angrily on his sister while walking the family’s small, fat dog in the Derbyshire hills. They had paused (as ever, to pick up the dog), when she asked chattily where he was off to next. “Really, Kathleen, you know you mustn’t ask me that,” he snapped, scanning the horizon for listening Nazis dressed as nuns.

Arguably, fear of fifth-columnists got hyped into paranoia. In 1940 a seaside landlady in Sandown was sentenced to death (commuted to prison) for pretending to be retrieving her dog from a prohibited beach while making sketch-maps of gun emplacements and having a secret swastika under her raincoat. Later evidence suggests that Dorothy O’Grady was a sad fantasist seeking excitement and revenge on an unhappy childhood and earlier convictions for pilfering and prostitution. But her maps – and cutting of phone-lines – were deadly accurate.

Arguably, fear of fifth-columnists got hyped into paranoia. In 1940 a seaside landlady in Sandown was sentenced to death (commuted to prison) for pretending to be retrieving her dog from a prohibited beach while making sketch-maps of gun emplacements and having a secret swastika under her raincoat. Later evidence suggests that Dorothy O’Grady was a sad fantasist seeking excitement and revenge on an unhappy childhood and earlier convictions for pilfering and prostitution. But her maps – and cutting of phone-lines – were deadly accurate.

The Careless Talk campaign was taken to heart by everyone. And thank goodness they did.

This article first appeared in THE JESTER issue 520

No comments yet.